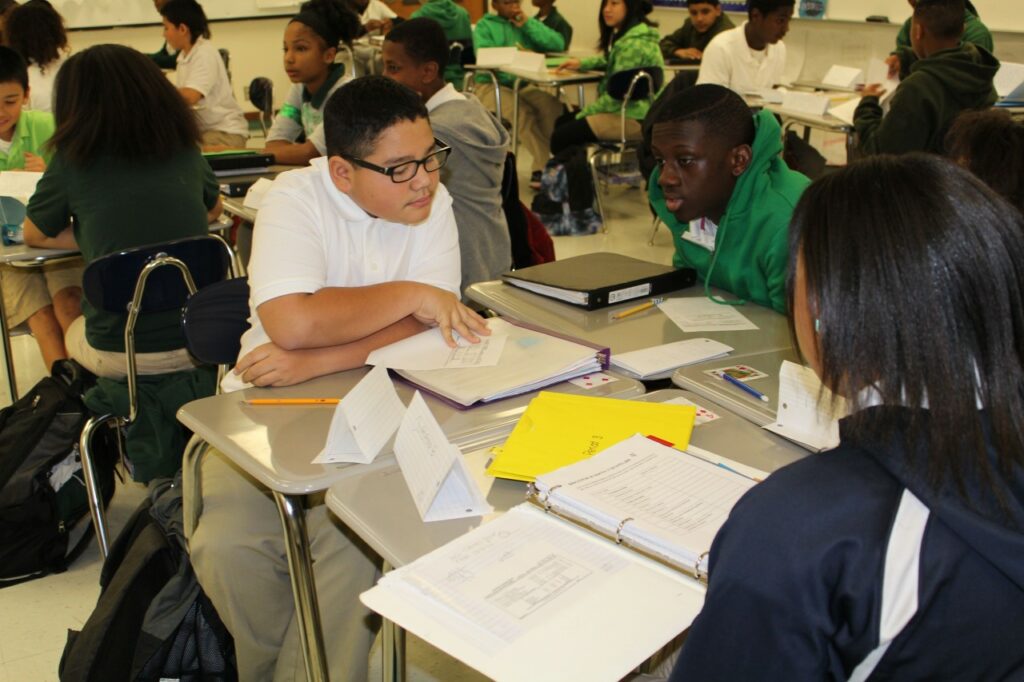

Susan Frey/EdSource Today

Susan Frey/EdSource Today Susan Frey/EdSource Today

Susan Frey/EdSource TodayDuring the five years since California adopted the Common Core State Standards for mathematics and English language arts, the search for high-quality textbooks and curriculum materials has been a sticking point, in some cases a major one, in effectively and speedily implementing the new standards.

That’s according to leaders in several school districts where EdSource is tracking Common Core implementation. School districts are making progress in finding and selecting the right materials, but the complicated effort is still underway in these districts and many others across the state.

“Preparation and timing of available resources has been the most difficult aspect of this rollout,” said Fresno Unified Superintendent Michael Hanson when the state released scores from the Smarter Balanced tests, which were based on the Common Core standards and administered last spring. After going through a months-long process of piloting new materials with 350 teachers, Hanson said, “we’re only now using appropriate math materials.”

Hanson is not alone. In four of six districts being tracked by EdSource (Fresno, Elk Grove, Garden Grove and San Jose Unified) as they implement the Common Core, district leaders said that finding appropriate instructional materials has been a significant obstacle to teaching classes aligned with the new standards.

“The biggest challenge has been the lack of textbooks and materials,” said Gabriela Mafi, superintendent of Garden Grove Unified in Orange County.

The root of the problem, argued Phil Daro, a principal author of the Common Core math standards, is that “districts tried to switch to the Common Core before there were any books aligned with them.”

That, however, was not the fault of districts. The state adopted the Common Core in 2010, but the State Board of Education only approved a recommended list of K-8 math textbooks and materials in January 2014 – and only did so two weeks ago for K-8 materials in English language arts. During that five-year period, students took new Smarter Balanced tests aligned with the standards.

Textbook publishers were slow to come up with materials that were fully aligned to the Common Core standards. In many cases, materials that were purportedly aligned with them were just hastily updated versions of older materials.

“In some situations I think publishers have taken a sticker and put it on the old set of standards and called it a Common Core book,” said Superintendent Chris Hoffman of Elk Grove Unified near Sacramento, in an interview with EdSource last spring.

By now, however, major textbook publishers have had time to develop materials that are more directly aligned to the Common Core standards. That is reflected in the fact that most of the materials on the state’s recommended lists for both English and math were produced by publishing giants like Pearson, Houghton Mifflin and McGraw-Hill.

Adding to the complexity of the textbook adoption process, California is ceding more authority to districts to pick their own materials, as are several other states. According to the American Association of Publishers, California is one of only 19 “adoption states” that “adopts” textbooks and instructional materials. But while State Board of Education still reviews and recommends materials for math and English in kindergarten through 8th grade, it doesn’t require districts to buy or use them.

As a result of the passage of AB 1246 in 2012, districts can choose their own materials for those grades, as long as they are aligned with the state’s academic content standards and involve teachers in the review process. Some other “adoption states” are moving in a similar direction, representing what an EdWeek report characterized as “a sea change in K-12 policy.”

At the high school level, California districts are free to adopt whatever curriculum materials they chose, as has always been the case. This is because the state constitution requires the State Board of Education to adopt instructional materials for grades K-8, but not for high school.

The challenges in finding appropriate textbooks and other instructional materials has affected districts’ abilities to implement the Common Core, according to some education leaders.

Garden Grove’s Mafi said her district chose not to introduce the Common Core ahead of what she described as “the state requirement” to implement the standards last year, in part because it didn’t have materials it needed to do so sooner. Mafi said the district also wanted more time to prepare teachers “and provide extensive professional development.”

The district “piloted” math textbooks from a list of materials recommended by the state for kindergarten through 8th grade from September 2014 through January 2015. The pilot consisted of teachers trying out the materials, then reviewing data as to their effectiveness, before recommending them to the district’s elected board of trustees for formal adoption.

Officials in other districts worried that the dearth of adequate materials affected classroom instruction – and added to the anxiety levels of teachers asked to take on yet another major reform. “Our biggest concern is that when teachers are frustrated and don’t have tools they need, they’re less effective,” said Jackie Zeller, San Jose Unified’s director of secondary curriculum, instruction and EL services in an interview earlier this year.

In many districts, teachers have been integrally involved in trying out new materials, adapting existing ones or creating their own, instead of waiting for the state to lead the way. They piloted textbooks and online resources, pored over existing materials to figure out which units were aligned to the new standards and collaborated with each other to discuss the best options to meet their students’ needs.

This represents a change from what often occurred under No Child Left Behind and other top-down reforms in which districts typically selected textbooks from state-adopted lists. These included materials like McGraw Hill’s Open Court Reading series, which laid out highly structured lesson plans, and which were very unpopular among many teachers who sought more creativity in their classrooms.

In Visalia Unified, the Common Core materials review process included setting up a large committee with teacher representatives from every school in the district. “This took many months and much discussion about the standards, the quality of the materials, and how to approach instruction,” Superintendent Craig Wheaton said. The materials his Central Valley district adopted, he said, “are designed to support teachers as they develop lessons. They are not meant to be all that they use.”

Discontent with curriculum materials emerged as a top issue among thousands of educators who attended the July 31 “Better Together” teachers summit held at 33 locations throughout the state. Kitty Dixon, senior vice president at the Santa Cruz-based New Teacher Center and one of the summit organizers, said many teachers who attended were frustrated by the lack of appropriate materials on the market – and consequently by the time and effort they spent pulling their own materials from the Internet.

Marci Gould, who teaches 4th grade at Buena Vista Elementary in Walnut Creek, said at the time her district had not yet adopted Common Core-aligned instructional materials. “My biggest concern is not having a set curriculum or text as a basis,” she said. “I spend a lot of personal time developing my own curriculum based off the Common Core standards.”

There are both pros and cons to these home-grown efforts. “Some of it is brilliant, some of it is goofy,” Daro said. But he said on the plus side these materials “will get better over time” and the process has had the benefit of deeply immersing more teachers both in mathematics and the Common Core standards to guide their instruction.

As districts sorted through materials that publishers claimed were aligned with the Common Core, some delayed adopting new materials and continued to use old textbooks.

“We’ve had to do some bridge work trying to use the existing texts with the new standards,” Elk Grove’s Hoffman said. “We made changes in mathematics this past year and did an English language arts adoption at the elementary level, so we’re still really early in this process of trying to put all these resources in place.”

Contrary to some other district leaders, Santa Ana Unified Superintendent Rick Miller said he was not overly concerned about the challenge of finding curriculum materials. In Miller’s opinion, more important than the materials is the quality of teaching going on in the classroom. “I think the primary instructional tool in the classroom is the teacher,” he said.

That view was similar to the opinion expressed by Aspire’s chief academic officer, Elise Darwish. “I’m pretty agnostic about materials,” she said. “I actually think it’s so much more about the teacher, the instruction and the assessments. I don’t want to say I don’t care about materials, but I think you can upgrade instruction, no matter what your materials.”

Ed Winchester, Santa Ana’s executive director of secondary curriculum and instruction, said the district initially decided in 2013 to refrain from adopting new mathematics materials. After spending a couple of months looking over what the market had to offer, he said, the district reviewers decided that those published materials were mostly “hastily adapted from…current programs.” “We just decided we were going to write a lot of our own curriculum and find materials that matched our needs,” he said.

Santa Ana ended up supplementing existing textbooks with four new, free online resources, which offer a range of support including downloadable K-12 lesson plans in mathematics and English language arts. These are: EngageNY, developed by New York’s Department of Education; materials from the Georgia Department of Education; and resources from the Silicon Valley Math Initiative and the Irvine Math Project.

This spring, Santa Ana will pilot Houghton Mifflin’s “Go Math” at seven elementary schools. At the same time, the district will continue to use open source and other digital materials.

For many districts, the state’s adoption of recommended lists for both the math and English language arts materials came too late to be useful – and left district staff members doing a lot of the heavy lifting themselves.

Hanson said Fresno Unified spent nearly $7.5 million on its K-8 math materials adoption and trained teachers last summer to implement the new instruction in 2015-16.

Adam Ebrahim, a literacy consultant with the Fresno County Office of Education, praised the way Fresno Unified found or created instructional materials. Teachers were allowed time to collaborate and search for resources that responded to their students’ needs, he said.

“If we want to really ramp up our classrooms, we have to empower teachers to design their own curriculum,” he said. “I understand the grumbling, but if teachers aren’t getting the time they need to do that, they should take it up in bargaining sessions.”

In theory at least, the process going forward for adopting math and English language arts textbooks should be easier, since the state has now adopted curriculum frameworks in both subjects, along with recommended lists of instructional materials. (The California Department of Education defines frameworks as “blueprints for implementing the content standards.”)

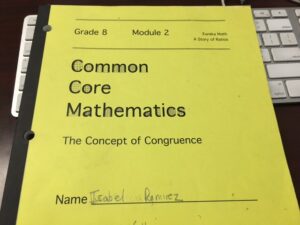

EdSource Photo

Common Core math textbook for 8th grade

But that does not mean the process for finding the right materials, and its outcome, is fully resolved. Concerns about the adequacy especially of math materials have been raised, among others, by William Schmidt, who runs Michigan State University’s Center for the Study of Curriculum, and Morgan Polikoff, an assistant professor at the University of Southern California’s Rossier School of Education. EdReports, a national nonprofit organization, has also issued a fierce critique of textbooks claiming to be Common Core-aligned, although the National Council of Teachers of Mathematics has strongly disputed its conclusions.

School districts are at various stages in trying out and implementing curriculum materials – some drawn from the state lists and some not.

In San Jose Unified, for example, teachers developed their own K-5 English language arts and math units with the support of WestEd, said Jason Willis, the district’s assistant superintendent of community engagement and accountability. The district is using two on-line programs to supplement the K-5 English language arts instruction and is supplementing its math instruction with materials created by TERC, a not-for-profit educational development organization.

The district’s middle schools piloted online English language arts instructional materials last year that were implemented this fall for intervention, long-term English learners and special needs students, Willis said. Middle school math teachers have been trying out College Board’s “Springboard” math curriculum which is on the state’s recommended list, and are going to recommend to the school board that it be adopted for use going forward. At the high school level Algebra 1, geometry and Algebra 2 classes have began using the “Springboard” curriculum as well.

What impact this patchwork of curriculum materials will have on student performance and instruction is as yet unknown. But State Board of Education member Patricia Rucker, a former teacher who is a legislative advocate for the California Teachers Association, said she believes progress has been made. The state, she says, now has high-quality math and English curriculum “frameworks,” as well as recommended materials to go with them.

At the state board’s most recent meeting in Sacramento this month, she acknowledged that getting to this point has taken longer to accomplish than many teachers anticipated and that students were assessed on the Common Core standards before the curriculum was fully implemented. “We did a lot of that work out of order,” she said. “And we didn’t really take time to really appreciate the work that had to be done at each stage.”

Katherine Ellison contributed reporting for this story.

To get more reports like this one, click here to sign up for EdSource’s no-cost daily email on latest developments in education.

Comments (10)

Comments Policy

We welcome your comments. All comments are moderated for civility, relevance and other considerations. Click here for EdSource's Comments Policy.

Gary Ravani 8 years ago8 years ago

The fact that there is some inherent illogic in the rollout of CCSS and SBAC is to be expected as the rollout (but not the CCSS or SBAC themselves) was more of a political issue rather than an educational one. I give the CDE and SBE some space here for that necessary maneuvering. This do to the fact that the SBAC scores were not going to be counted for accountability purposes immediately. Even the relatively … Read More

The fact that there is some inherent illogic in the rollout of CCSS and SBAC is to be expected as the rollout (but not the CCSS or SBAC themselves) was more of a political issue rather than an educational one. I give the CDE and SBE some space here for that necessary maneuvering. This do to the fact that the SBAC scores were not going to be counted for accountability purposes immediately. Even the relatively short hiatus of “accountability” was roundly and loudly criticized by the self-appointed advocates for students, pundits, editorialists, and some politicians of a certain persuasion. To take a full three years off to account for the rollout of CCSS aligned curriculum and reasonable time for professional development, and then administration of SBAC, would have triggered a political firestorm that could have engulfed the entire effort. Granted, some would say this would be a good thing.

Others would suggest that the old CST questions could have been triaged in a way that could have left them closer to CCSS alignment, but the whole idea was to ditch the old bubble-in format as well as the misguided API/AYP style “finger-point and punish” pseudo-accountaibilty system that the National Research Council, as well as other legitimate authorities, assert had little to no positive outcomes for education and many negatives for learning. The CSTs also had significant issues with reliability even after being in place for years, and what a modified version (as untested as SBAC) would do for validity and reliability is, at best, a guess.

All in all, the whole implementation of CCSS and SBAC was flawed. The only good thing is it was not as demonstrably as flawed as the system that was in place. And, much of the energy for the system employed was driven by politics with a great deal of noise generated by those whose real commitment to education is problematic. Therefore, being ‘flawed” is a given.

Bill Younglove 8 years ago8 years ago

Thanks for addressing aspects of the implementation of the Common Core. Getting text(book) available materials in place sure will help, so that the next round of SBAC (or PARCC, or whatever) testing will make (more) sense. Still, that 1073 page ELA/ELA Framework, despite ongoing rollputs, is formidable, indeed.

zane de arakal 8 years ago8 years ago

Strictly, cart before the horse!

Jonathan Raymond 8 years ago8 years ago

One of the most compelling challenges and opportunities of the new standards are the instructional shifts they require our teachers to make. They must be learners, designers, developers, and collaborators. This requires investments in resources, persistence, and patience. The state has provided initial investments in these areas but when you take into the account what is needed for instructional learning, technology, and materials it is only a down payment and will require … Read More

One of the most compelling challenges and opportunities of the new standards are the instructional shifts they require our teachers to make. They must be learners, designers, developers, and collaborators. This requires investments in resources, persistence, and patience. The state has provided initial investments in these areas but when you take into the account what is needed for instructional learning, technology, and materials it is only a down payment and will require ongoing significant state resources and investments if we want our teachers and children to be successful. Moreover, organizations like Ed Reports, which utilize highly skilled educators to review materials and text books to validate their alignment to the content and sequence of the new standards, can eliminate much of the guess work and/or confusion that comes from dealing with materials purchases from the major publishers. What also should not be lost is the need to align professional learning with the sequence AND material needs afforded by the new standards. Currently this does not exist.

Replies

Don 8 years ago8 years ago

It seems to me what you’re saying, Mr. Raymond, is that most teachers weren’t nearly ready to teach Common Core last year, but the state went ahead and required it nevertheless. This matches up with much of the criticism that school districts weren’t ready for showtime.

Ann 8 years ago8 years ago

The root of the problem, argued Phil Daro, a principal author of the Common Core math standards, is that “districts tried to switch to the Common Core before there were any books aligned with them.” We'll see, Phil. How long should we wait for positive results? Read through these comments, all before we saw the horrible math results on the SBAC. I work with elementary and there is little emphasis on math fluency in facts and 'standard' … Read More

The root of the problem, argued Phil Daro, a principal author of the Common Core math standards, is that “districts tried to switch to the Common Core before there were any books aligned with them.”

We’ll see, Phil. How long should we wait for positive results?

Read through these comments, all before we saw the horrible math results on the SBAC. I work with elementary and there is little emphasis on math fluency in facts and ‘standard’ algorithms. Rather the students are taught elaborate methods of solving relatively simple problems that can only be described as more complex and unwieldy psuedo-algorithms. I simply don’t see the students gaining any grand conceptual understanding. Moreover they are hamstrung when they need to advance to new concepts that require prior ability.

http://edsource.org/2015/parents-try-their-hand-at-common-core-math/73161

Doug McRae 8 years ago8 years ago

State Board member Rucker is absolutely correct noting that California initiated statewide assessments on the Common Core before Common Core instruction was suitably implemented. That violated the widely accepted sequence for implementing any new set of content standards for K-12 education: Instruction first, followed by Assessments, then Accountability. The consequence of this misstep is that the initial 2015 Smarter Balanced assessment results are invalid unreliable and unfair, not to mention virtually uninterpretable and unuseful. … Read More

State Board member Rucker is absolutely correct noting that California initiated statewide assessments on the Common Core before Common Core instruction was suitably implemented. That violated the widely accepted sequence for implementing any new set of content standards for K-12 education: Instruction first, followed by Assessments, then Accountability. The consequence of this misstep is that the initial 2015 Smarter Balanced assessment results are invalid unreliable and unfair, not to mention virtually uninterpretable and unuseful. As Dave Gordon [SacCo Supt] said so succinctly Feb 2014 in the SacBee “It just isn’t fair to test students on material they haven’t been taught.”

If a classroom teacher has a final exam that includes material not taught during the course, that teacher will get deserved pushback from students and parents and likely earn a reprimand from administrators. Sacramento K-12 education leaders deserve the same pushback from students, teachers, administrators, parents, legislators, media, and taxpayers for implementing statewide assessments measuring the Common Core before many many students had the opportunity to learn Common Core material, that is, before Common Core instruction was implemented by many many California local school districts.

Replies

Ann 8 years ago8 years ago

Doug, last year was the third year out district used Engage New York. Taking into account the critics of the ‘new’ CC curriculum, how long (how many students) should wait for a determination the rebirth of constructivsm is ‘working’?

Doug McRae 8 years ago8 years ago

Ann -- A generic answer to your question how long should it take for a new curriculum to be evaluated by test scores, I would say at least 3 years and in some cases maybe 4-5 years if the picture isn't clear after 3 years. But, if your district already has 3 years under their belt with Engage NY, they certainly are ahead of the curve in California for implementing CC instruction. That would start Engage … Read More

Ann — A generic answer to your question how long should it take for a new curriculum to be evaluated by test scores, I would say at least 3 years and in some cases maybe 4-5 years if the picture isn’t clear after 3 years.

But, if your district already has 3 years under their belt with Engage NY, they certainly are ahead of the curve in California for implementing CC instruction. That would start Engage NY Sept 2012 to get three years under their belt by spring 2015. Statewide, while CA adopted the CC Aug 2010, Sacramento didn’t have a dime to spend on implementation until summer 2012 and most districts were in a similar fiscal condition. The Curriculum Commission was dark from 2009 until May 2012 when it was revived as the Instructional Quality Commission, and began the work of providing curriculum frameworks and recommending instructional materials for CC Math (textbooks approved Jan 2014) and ELA/ELD (textbooks approved Nov 2015), with then usually several years for local districts to adopt and conduct teacher professional development for the locally adopted materials, as the post notes. Your Engage NY experience is clearly ahead of the curve.

In addition, we don’t have statewide assessment data for your district to access for your 3-year implementation period. CA gave the old non-CC STAR CSTs in 2013, went dark in 2014 to conduct the Smarter Balanced Field Test, and gave the new Smarter Balanced test with its questionable results in 2015. No independent external data with which to evaluate use of Engage NY for those three years. Unless your district has other assessment data [I would not call internal Engage NY tests a reasonable source for independent program evaluation purposes], you don’t have comparable data for the 3 years you’ve implemented Engage NY.

So, 3-5 years in general, if you have reasonable data upon which to do the evaluation.

Kristen Thompson 8 years ago8 years ago

Ann, I totally agree. There is way too much that’s unknown and untested here. I am very worried that my kids won’t be prepared for high school and college. We are relying on “best guess” as far as how Common Core will affect our kids.