Credit: Allison Shelley for American Education

Credit: Allison Shelley for American Education Credit: Allison Shelley for American Education

Credit: Allison Shelley for American EducationFor the next three years, every superintendent needs to focus on improving middle school math.

Performance on California’s 2022 Smarter Balanced scores dropped 6.5% in math and 4% in English language arts (ELA). National Assessment of Education Progress (NAEP) scores, released the same day, also showed larger declines in math than in reading. In eighth grade math, California had seemingly good news on NAEP: students declined, but less than the U.S. average. This confirms much of the research on the pandemic’s effect on student learning.

But for all their insight, these reports and studies don’t reveal the calamity in middle school math because they never follow the same groups of students over time as they move through school. Buried in these averages is some crucial variation: California’s middle school math students were struggling before the pandemic, and they have been the group most negatively affected by it. Their slide in math is three times the size of the decline of the same students in English language arts.

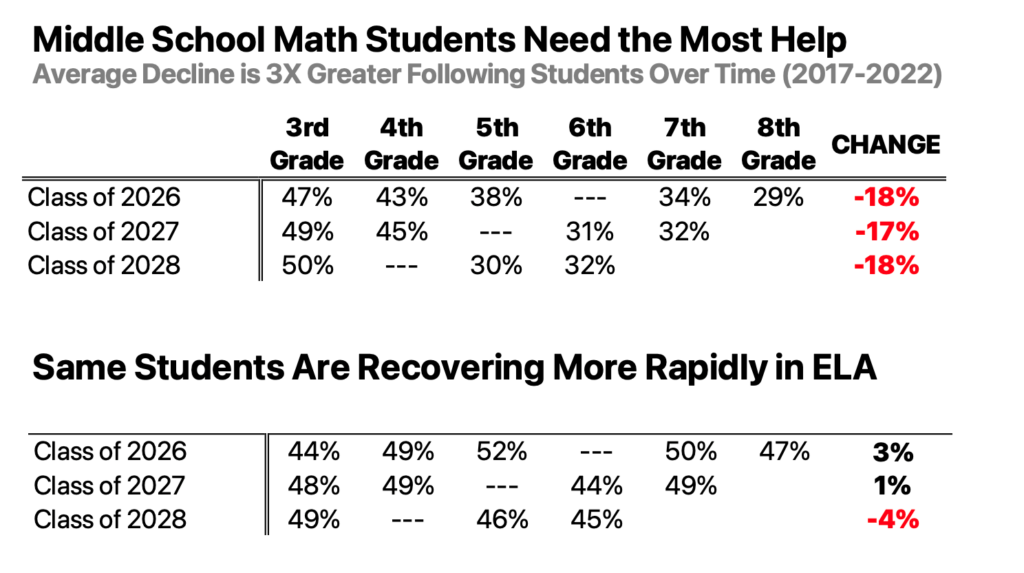

The table below organizes Smarter Balanced data by when students will eventually graduate from high school. The Class of 2026 were third-graders in 2017, and their schooling was interrupted in 2020 when they were in sixth grade. Only one-quarter of students were tested in 2021, and it wasn’t until last year that testing was back to normal.

Looking at the data by each class from 2017-19 and 2021-22, the decline in math worsens as students move through middle school, averaging -17%. In English language arts, the average change is zero, as some of the students have improved since their third grade starting points.

Source: California Department of Education (https://caaspp.cde.ca.gov/)

Subsequent elementary classes (not shown here) lack third grade baselines, so they’re tough to evaluate. We do know from research by diagnostic testing companies such as NWEA and Curriculum Associates, that early elementary students have made up ground in reading in the past year.

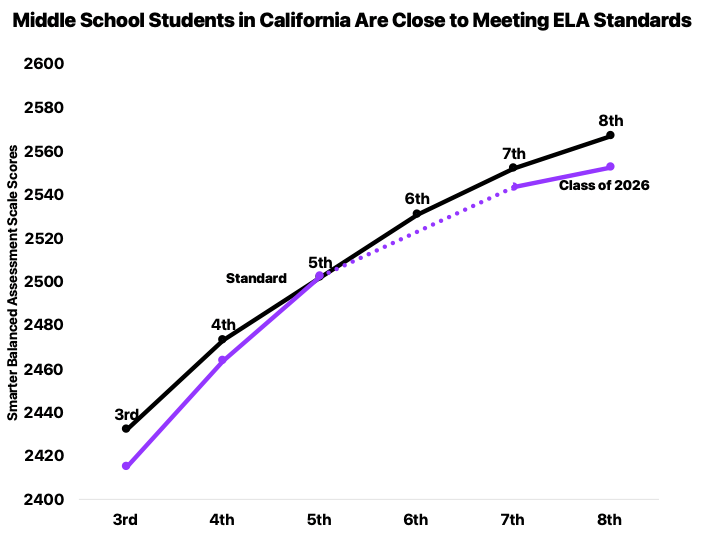

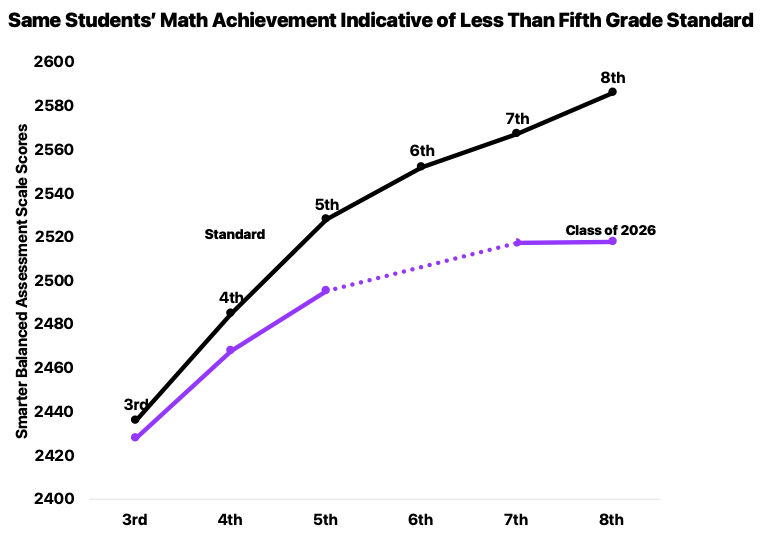

California also publishes vertical scale scores on the Smarter Balanced tests, which trace over time the progress of all students, not just those scoring proficient. Focusing again on last year’s eighth graders (the Class of 2026), you can see that in ELA, they are approaching state standards. In math, the typical eighth grade student had achievement indicative of the fifth grade standard. Once again, the pandemic took a previously obscured problem in middle school math and made it more severe.

Source: California Department of Education (https://caaspp.cde.ca.gov/)

Source: California Department of Education (https://caaspp.cde.ca.gov/)

Middle school math is uniquely difficult because it’s where students need to master fractions and decimals. Students’ knowledge of fractions is so essential, it predicts overall math achievement in high school six years later. Hung Hsi-Wu, professor emeritus of mathematics at UC Berkeley, writes that the proper study of fractions and decimals provides a steady ramp that leads students from arithmetic gently up to the abstraction of algebra. But when students don’t learn fractions well, the ramp collapses and becomes a ninety-degree wall. Poor knowledge of fractions may lead students to give up trying to make sense of mathematics.

Districts have the financial resources for recovery, and wise advice has clustered around four suggestions about what’s best to do: high-dosage tutoring, professional learning for teachers, expanded time in school, and a shift to mastery learning. Assuming you’re doing them, here are four implementation questions to guide your district’s efforts.

How many middle school students have high dosage tutoring in math?

Tutoring is one of the most powerful interventions available, with a large body of research showing the benefits of higher graduation rates, reduced absenteeism and the ability to close half a year’s gap in learning. But it must be done right.

Early data suggests even well-intentioned states and districts are having trouble setting up tutoring correctly. It must be built into the school day, not after school. Students need to meet consistently two-to-three times a week in small groups (not necessarily 1:1), with the same trained tutor using clear lesson plans.

How much of your professional learning for middle school math teachers emphasizes improving teaching first?

You might be tempted to work on strengthening teachers’ math content knowledge first. But new research from Harvard and Brown University says it’s more important to work on math-specific teaching practices first. To do this, it might make sense for your teachers to participate in CORE’s online course to learn about new teaching methods for helping students make sense of fractions.

How many middle schools in your district have added more time or double-dose courses in math?

Over a year, a double dose of math course has been shown to produce gains equivalent to a quarter-year of extra learning. If that seems too difficult, why not make every middle school math class at least an hour long?

Where are your middle schools in the shift to mastery learning?

Michael Horn writes in his book From Reopen to Reinvent that emerging from the pandemic, learning must be fixed and time needs to be variable. With middle school students as much as three years below grade level in math, they need a system that shows them how far along they are to mastering learning goals.

Lindsay Unified has some helpful videos on how they’ve implemented what they call self-directed learning. Summit Public Schools in the Bay Area uses self-directed learning cycles, though full implementation requires wholesale changes. Khan Academy and NWEA’s MAP Accelerator has helped struggling math students achieve better than expected growth by giving them personalized learning paths. MasteryTrack offers schools free dashboards to ease the shift to seeing which learning objectives have been met.

Even though literacy achievement is rebounding faster, no district is where it needs to be. Seventy percent of the jobs by 2030 will require at least some college, according to projections by Moody’s chief economist, Mark Zandi. Every leader’s goal should be 70% of students proficient, which means they’re on track to being college and career ready. It’s not 100%, but 70% is a meaningful and challenging goal.

When everything seems like a crisis, it’s hard to set priorities. The data here shows we have tens of thousands of students in our care who are on the verge of being functionally unable to use math in the real world. Middle school math must be elevated to the top of every instructional leader’s list.

•••

David Wakelyn is a partner at Union Square Learning, a nonprofit that works with school districts and charter schools to improve instruction. He previously was on the team at the National Governors Association that developed Common Core State Standards.

The opinions expressed in this commentary represent those of the author. If you would like to submit a commentary, please review our guidelines and contact us.

To get more reports like this one, click here to sign up for EdSource’s no-cost daily email on latest developments in education.

Comments (6)

Comments Policy

We welcome your comments. All comments are moderated for civility, relevance and other considerations. Click here for EdSource's Comments Policy.

SFUSD Middle School Teacher 4 months ago4 months ago

I'm concerned about this article. It seems like it's a call to double-down on pedagogical practices that are not supported by statistically valid, or appropriately designed studies (i.e. those stemming from the Boaler, et. al. education camp). It also seems like privatization efforts - in the form of for-profit and "non-profit" course$, training$, resource$, etc. - are being touted as the fix to the problem in middle school math courses. Have we learned nothing over … Read More

I’m concerned about this article. It seems like it’s a call to double-down on pedagogical practices that are not supported by statistically valid, or appropriately designed studies (i.e. those stemming from the Boaler, et. al. education camp). It also seems like privatization efforts – in the form of for-profit and “non-profit” course$, training$, resource$, etc. – are being touted as the fix to the problem in middle school math courses. Have we learned nothing over the last twenty years? The edu-grifters are at it again, it seems.

What I’ve see over the last 15 years in SFUSD is a steady, slow decline in mathematical skills. This time-frame correlates with adoption of Common Core standards and teaching guides and the wholesale implementation of pedagogical methods rooted in ideology rather than sound research. SFUSD has adopted – without any kind of comparative controls – the poorly designed and outright academically fraudulent methodologies of Dr. Jo Boaler and her cronies.

For the past 10 years I have seen a disturbing number of 8th grade students enter 9th grade without their multiplication facts memorized, without fluency in solving 1-step and two-step equations, a completely inability to perform operations with fractions and decimal numbers, and almost no ability to work independently or take individual assessments.

This is a direct result of teacher training programs and administrators implementing SFUSD’s middle school math curriculum.

But let’s double down on some more bad pedagogy and spend million$ on ed-tech. That’ll fix it.

Cathy Kessel 6 months ago6 months ago

"You might be tempted to work on strengthening teachers’ math content knowledge first. But new research from Harvard and Brown University says it’s more important to work on math-specific teaching practices first. To do this, it might make sense for your teachers to participate in CORE’s online course to learn about new teaching methods for helping students make sense of fractions.” This summary of research on professional development from a different source is more specific: "My LPI … Read More

“You might be tempted to work on strengthening teachers’ math content knowledge first. But new research from Harvard and Brown University says it’s more important to work on math-specific teaching practices first. To do this, it might make sense for your teachers to participate in CORE’s online course to learn about new teaching methods for helping students make sense of fractions.”

This summary of research on professional development from a different source is more specific:

“My LPI colleagues and I screened the literature for high-quality studies that found professional-development models that changed teacher practice and enabled student-learning gains. We found that these models had a number of features in common: They were based in the curriculum content being taught; engaged teachers in active learning as teachers tried out the practices they would use; offered models of the practices with lessons, assignments, and coaching; extended over time (typically at least 50 hours of interaction over a number of months) with iterative opportunities to try things in the classroom and continue to refine. In addition, these efforts were almost always accompanied by in-person or on-line coaching, sometimes using classroom videos as the grist for those conversations.”

See https://www.edweek.org/teaching-learning/opinion-linda-darling-hammond-wins-international-prize-for-education-research/2022/11

Jim 7 months ago7 months ago

A great article. Longitudinal assessment is the best way to look at attainment or lack thereof and provide targeted intervention. However teachers unions hate longitudinal assessment as it can also be used to determine teacher effectiveness.

Faye Johnson 7 months ago7 months ago

Interesting article. I believe cohort analysis is absolutely essential. School districts have this data, but I don't know how many of them do cohort analysis or have the tools and personnel to do this type of study. I'd suggest adding another consideration. Compare cohort performance in language arts to mathematics. I had the opportunity to do this in a small district in which the majority of students go through the system as a cohort from … Read More

Interesting article. I believe cohort analysis is absolutely essential. School districts have this data, but I don’t know how many of them do cohort analysis or have the tools and personnel to do this type of study. I’d suggest adding another consideration. Compare cohort performance in language arts to mathematics. I had the opportunity to do this in a small district in which the majority of students go through the system as a cohort from pre-K through high school graduation. I wanted to see if efforts in high school were making a difference. Three years of high school made a significant difference in Language Arts with the 15% of students meeting/exceeding standards in 8th grade increasing to 55% meeting/exceeding in 11th grade. Three years of high school did not make as much of a difference in mathematics, however, with the 9% of students in the 8th grade meeting/exceeding standards increasing to only 12% by the end of 11th grade.

Put another way, students persisted in Language Arts and became successful; students did not persist in Mathematics and achievement remained the same. I believe this bears analysis statewide.

Replies

Jing Wu Harrison 7 months ago7 months ago

Thank you for sharing your analysis and finding.

Ben Rush 7 months ago7 months ago

Finally, someone follows the data of a year-group. This the true indicator of the quality of public school K-12 education in California. Have been trying convince my unified school district to follow year-groups since the STAR.