Credit: Unsplash

Credit: Unsplash Credit: Unsplash

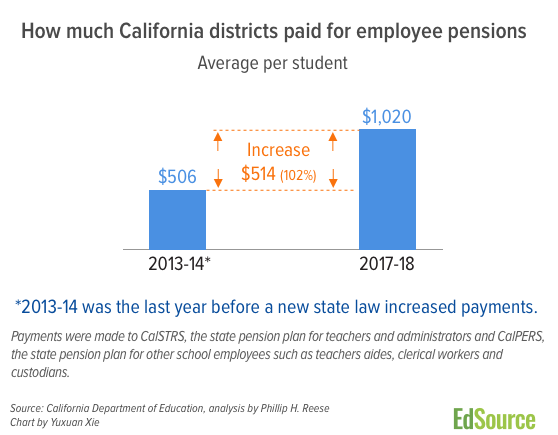

Credit: UnsplashCalifornia school districts’ expenses for employee pensions on average doubled to about $1,000 per student over the four years ending in 2017-18, according to newly released state data. Those increases will rise at least several hundred dollars more per student before stabilizing two years from now.

The Legislature mandated the increases, partly to make up for the sharp decline in the value of the pension funds for school employees and other public workers during the Great Recession in 2008.

The average cost per student in California rose from $506 per student in 2013-14 to $1,020 in 2017-18, an increase of 102 percent. However, there are significant differences among districts’ increases, especially for small districts. Some small elementary districts saw a decrease.

Rising pension costs will continue eating up a significant portion of new state revenue that districts could use in other ways, such as expanding academic programs, hiring school nurses and school counselors, or raising teachers’ pay. Higher costs may also erode the goal of equity that underlies the state’s Local Control Funding Formula. While the funding formula distributes additional money to districts with high proportions of low-income children and English learners, those districts are not spared the burden of escalating pension costs.

“As we work with districts around the state, we are worried that the pension increases are undermining the equity promise of the funding formula,” said Arun Ramanathan, chief executive officer of Pivot Learning Partners, a nonprofit that works with school districts on strategic changes. “Districts are being placed in an increasingly untenable situation where they have to choose between funding pensions or services for high-needs students.”

Later this month Pivot will release a report on the impact of increasing pension costs on educational equity.

In 2013, the Legislature, at Gov. Jerry Brown’s urging, passed a law to rescue the state’s two public employee pension funds from possible insolvency. A year later, lawmakers mandated seven consecutive years of rate increases for the California State Teachers’ Retirement System, or CalSTRS, the teachers’ and administrators’ pension fund.

About three-quarters of school districts’ pension obligations go to CalSTRS. The rest goes to the California Public Employees’ Retirement System, or CalPERS, the nation’s biggest public pension fund. CalPERS handles pensions for other school employees, such as teacher aides, secretaries and custodians, along with state, county and city public employees. The Legislature sets CalSTRS rates, while CalPERS’ board of trustees sets its own rates.

Pensions have been one of the fastest-rising costs in school budgets. Before passage of the new rates, districts statewide paid $2.8 billion in 2013-14 to CalSTRS and CalPERS. Four years later, those costs had nearly doubled. Pension expenses consumed about 8 percent of K-12 districts’ budgets in 2017-18 and will rise to an estimated 11 percent in 2020-21.

Districts, the state and teachers/administrators share pension costs, although districts are responsible for an increasingly larger portion. Contribution rates are calculated as a percentage of total employee payroll. So although the rates are uniform statewide, districts that pay teachers the highest salaries will make the biggest pension payments. Salaries at high school districts generally are higher than at elementary school districts.

Districts with lower pay scales or that continually hire a large proportion of new teachers at beginner’s pay will tend to have pension expenses below the statewide average. Pension costs per-student are higher at districts with declining enrollment.

Since 2014-15, Santa Clara Unified and Madera Unified had among the biggest increases in per-student pension costs — for different reasons.

Santa Clara Unified, a 14,700-student district in the Bay Area, paid $1,554 per student in pension costs in 2017-18, an increase of 183 percent over four years and more than $500 per student above the statewide average. The district took advantage of a surge in property tax revenue after Gov. Jerry Brown dissolved local redevelopment districts that had siphoned off revenue that is now being reverted to schools and local governments. The district raised previously frozen teacher salaries to be competitive with the highest-paying districts in Santa Clara County and hired back and added new staff, including counselors, said Eric Dill, Santa Clara Unified’s chief business official. Pension costs rose proportionally as a result.

“Every percent additional to CalSTRS costs $1 million that we would have invested in programs and to strengthen instruction, but it’s an obligation we have to pay,” Dill said.

Madera Unified, a 19,000-student district in the Central Valley, was a big beneficiary of the Local Control Funding Formula, which took effect in 2013-14 and provided significantly more money to districts with large numbers of low-income students, English learners, foster children and homeless youth. In Madera Unified, 90 percent of students are English learners or from low-income families. Between reinstating jobs cut during the recession and hiring new positions, Madera added 277 staffers over four years and narrowed the pay gap with other unified districts. Pension costs per student rose 135 percent — $536 per student, from $404 to $950 in 2017-18.

Garden Grove Unified, the state’s 12th-largest district, saw its enrollment drop 8.5 percent over four years and its per-student pension cost rise 121 percent, from $489 to $1,078.

“By 2021, we will be paying $34.7 million more each year in increased retirement contributions than we did in 2013,” said Garden Grove Superintendent Gabriela Mafi. “This massive cost impacts all aspects of district operations from student programs to staffing. It especially impacts districts, such as ours, with high levels of teacher retention and longevity. We hope the state will continue to examine ways to address this growing concern.”

San Diego Unified, the state’s second-largest district with about 100,000 students, saw pension costs grow at one of the state’s slowest rates: a 78 percent increase over four years, from $613 per student to $1,092. A couple of factors accounted for that, said Debbie Foster, executive director for financial planning and development for the district. By using proceeds from the sale of property that the Legislature permitted during the recession, San Diego staved off layoffs and salary cuts. It had already achieved stability when revenue picked up after 2013-14 and other districts rehired teachers, she said. Then, in 2017-18, the district offered an early retirement package, taken by a number of veteran teachers earning at the high end of the pay scale, she said.

Fruitvale School District, with 3,300 students in grades K-8 in Kern County, represents a district in the middle. The 102 percent increase mirrored the statewide growth over four years — although in terms of dollars, the $807 per student it paid in 2017-18 was $200 below the average.

The impact of rising pension costs is “huge but it’s something we have known about,” said Fruitvale Superintendent Mary Westendorf. It was easier to absorb coming out of the recession, when state funding for schools far exceeded pension costs, but looking ahead to only cost-of-living adjustments in the state funding formula, “we’re trying to stay ahead of the downturn and avoid layoffs,” she said.

Causes for the increases

CalSTRS and CalPERS rely primarily on investment income earned from contributions to pay teachers and other employees’ pensions once they retire. Districts’ contributions have soared, in part because both pension funds’ investments lost about 25 percent of their value during the Great Recession. Once investments fall that far, it is difficult to make up for lost income, even though the stock market rebounded.

On top of that, recognizing that its earnings forecasts had been too optimistic, CalSTRS over the past decade cut its expected annual rate of return on investments from 8 percent to 7 percent — a significant change that then shifts the burden by requiring districts to pay higher contributions. A third factor was a recalculation of pension obligations because teachers are living longer.

The combination of a plunge in market value, an overly optimistic rate of return and changing actuarial assumptions has created a massive unfunded pension liability of $107 billion for CalSTRS as of June 30, 2017. That’s the shortfall CalSTRS faces in meeting its payout responsibilities to retirees over the next 30 years. If CalSTRS ever did run out of money, pensions would have to be paid out of the state’s general fund.

“By assuming too high a rate of return, California has consistently under-reported the level of funding that is required to pay for promised benefits,” Cory Koedel, an associate professor of economics and public policy at the University of Missouri, wrote in Pensions and California Public Schools, a report for Getting Down to Facts, a 2018 research project by Stanford University and the nonprofit PACE on California’s education policies and needs. “California has dug itself into a hole with CalSTRS, a hole that cannot be refilled.”

California is one of several states whose teachers don’t pay into the Social Security system; they are dependent on CalSTRS pensions. Koedel concluded that retirement benefits for California teachers are “within the norms of teacher plans in other states.” Teachers who retire at 60 after 25 years in the classroom would annually receive 50 percent of their final pay; that would increase to 60 percent if they had taught 30 years.

Escalating payment rates

Before the Legislature raised contributor rates in 2014, districts, the state and teachers together were paying 21.5 percent of payroll as pension contributions. By 2022-23, it will be 40 percent.

As the employer, districts are bearing the brunt of the increase to CalSTRS: from 8.3 percent before the reform law to a scheduled 19.1 percent of payroll, or 230 percent more, in 2020-21, continuing at that level through 2022-23.

In the state budget he introduced in January, Gov. Gavin Newsom is proposing the state pay for $700 million of districts’ scheduled increases to CalSTRS over the next two years. That would lower the state’s share in 2020-21 slightly, by a percentage point, and save districts about $120 per student over two years. However, a portion of the savings would be plowed back into pension payments if districts used the money to raise staff pay.

A conservative estimate is that districts’ payments to CalSTRS will be about an additional $275 per student by 2020-21, about $1.5 billion more. The total increase for both CalSTRS and CalPERS is harder to project, since CalPERS’ board of administration sets contribution rates annually. CalPERS’ most recent projection said rates could rise significantly.

Meanwhile, three years ago, teachers’ contributions to their own pensions reached the maximum of 10.3 percent, up from 8 percent of their pay. That increase was limited because the California Supreme Court, in a series of decisions over decades, ruled that public pension benefits in effect on the date of hire are a contract creating a vested right for employees. Existing benefits can’t be cut and contributions can be raised only if there is an additional benefit of comparable worth.

Attorneys for county and city governments are seeking to overturn the decisions, known as the California Rule, in several cases now before the court. For now, school districts and other public employers have few options.

“These required increases in contributions are inevitable and present potentially more severe equity challenges to an already inadequate system of finance,” wrote Christopher Edley, president of the Berkeley-based Opportunity Institute, in an analysis for Getting Down to Facts.

To get more reports like this one, click here to sign up for EdSource’s no-cost daily email on latest developments in education.

Comments (12)

Comments Policy

We welcome your comments. All comments are moderated for civility, relevance and other considerations. Click here for EdSource's Comments Policy.

John Steele 4 years ago4 years ago

Jerry Brown also mandated that cities and counties had to cough up an additional 50% more in contributions without those sources being identified. So that’s where we see all kinds of new taxes and library ballot measures that really just dump the money raised straight into the general fund were it can be siphoned off without much notice.

Dave Huff 4 years ago4 years ago

Ain’t liberalism grand?

jskdn 4 years ago4 years ago

Pre-PEPRA hires, 2% at 60 members, a large majority of current teachers, can get more than 2% per year of their final salary per year of employment, according to “CalSTRS Fundamentals”, 30 years of credited service increases age factor by 0.2 percent to a maximum of 2.4 percent. These are the examples given: "Fewer than 30 years 55-1⁄2 1.460 58-1⁄2 1.820 61-1⁄2+ 2.200 30 years or more 55-1⁄2 1.660 58-1⁄2 2.020 61-1⁄2+ 2.400" If you began teaching at … Read More

Pre-PEPRA hires, 2% at 60 members, a large majority of current teachers, can get more than 2% per year of their final salary per year of employment, according to “CalSTRS Fundamentals”, 30 years of credited service increases age factor by 0.2 percent to a maximum of 2.4 percent. These are the examples given:

“Fewer than 30 years

55-1⁄2 1.460

58-1⁄2 1.820

61-1⁄2+ 2.200

30 years or more

55-1⁄2 1.660

58-1⁄2 2.020

61-1⁄2+ 2.400”

If you began teaching at 25 and retired at the maximum factor it would be 2.4% x 36.5 or 87.6%.

el 4 years ago4 years ago

I think there is some confusion in the comments about how districts pay into CalSTRS. Payments from districts are a percentage of the "current" payroll. Not the past. So, a district that has a younger or smaller staff is paying less money for its CalSTRS contribution than it would if the staff was larger or higher on the step-and-column chart. The number of former teachers currently drawing benefits is not a factor in what districts are … Read More

I think there is some confusion in the comments about how districts pay into CalSTRS.

Payments from districts are a percentage of the “current” payroll. Not the past. So, a district that has a younger or smaller staff is paying less money for its CalSTRS contribution than it would if the staff was larger or higher on the step-and-column chart. The number of former teachers currently drawing benefits is not a factor in what districts are charged.

Early retirement incentives save the district money – or else they are not allowed to offer them. They save money by replacing a more senior teacher salary with a younger teacher salary.

It’s absolutely true that salary increases include this hidden CalSTRS tax. (CalPERS as well.) By contrast, increasing the district’s contribution to health insurance does not do that.

The cost here is significant, was created by the Legislature, and is an unfunded mandate on school district general funds that is causing significant budgetary pain for districts all across the state, whether they gave raises or not. It is significantly eroding the purchasing power of the per student LCFF base grant.

Michael Keeley 4 years ago4 years ago

The author makes a common mistake: STRS is underfunded because the CA legislature contributed less than "normal cost" during the great recession. Normal cost is the Defined Benefit pension term for the amount that should be contributed based on projected salaries and pensions, using the assumed rate of return. CA like most states must have a balanced budget, but there is no law requiring it to contribute Normal cost each year--by definition, … Read More

The author makes a common mistake: STRS is underfunded because the CA legislature contributed less than “normal cost” during the great recession. Normal cost is the Defined Benefit pension term for the amount that should be contributed based on projected salaries and pensions, using the assumed rate of return. CA like most states must have a balanced budget, but there is no law requiring it to contribute Normal cost each year–by definition, the amount due in any given year is what the legislature says is due. We certainly lost money during the great recession, but valuations eventually came back. LA City and LA County always contribute Normal Cost to their own plans each year. At STRS, the only way to recoup the missing contributions, and the 7+% return those contributions are assumed have yielded from the date due, is through dramatically increased assessments against Districts.

Terry 4 years ago4 years ago

Couldn't we stop framing this as a "school district" "teacher" problem and start framing this as a California pension system problem???? Teachers are state employees, paid via taxpayer dollars, just like policemen, firefighters, and all the other state employees who work for all the other state agencies like EDD, DMV, SCO, etc. Stop making it a "school district problem" and make it about how to ensure a viable pension system for all state … Read More

Couldn’t we stop framing this as a “school district” “teacher” problem and start framing this as a California pension system problem???? Teachers are state employees, paid via taxpayer dollars, just like policemen, firefighters, and all the other state employees who work for all the other state agencies like EDD, DMV, SCO, etc. Stop making it a “school district problem” and make it about how to ensure a viable pension system for all state employees.

SD Parent 4 years ago4 years ago

The real losers in these rising pension costs are the students in school today, where a significant percentage of the money earmarked for their education is being diverted to pay for poor fiscal management of CalSTRS and a resistance to increase employee rates so as to contribute more to the "normal cost" (the estimated annual cost of providing promised retirement benefits for current workers based on assumptions about return on assets, life expectancy of members, … Read More

The real losers in these rising pension costs are the students in school today, where a significant percentage of the money earmarked for their education is being diverted to pay for poor fiscal management of CalSTRS and a resistance to increase employee rates so as to contribute more to the “normal cost” (the estimated annual cost of providing promised retirement benefits for current workers based on assumptions about return on assets, life expectancy of members, etc.). I applaud the Governor’s idea to pay down the pensions, but it should come with a caveat: any district accepting the funds should agree to a moratorium on employee pay increases because it’s not clear that school districts will be fiscally responsible with the funds, particularly under growing pressure from teachers’ unions.

Despite a lower-than-average pension increase, SDUSD leadership whines incessantly about the increased pension costs – and how the state isn’t providing enough funding – and has used that to justify cuts made to student programs and services every year. What Debbie Foster failed to mention is that in the school year the district offered that huge early retirement program (2017), the district was operating with a budget that included deficit-spending of $91 million, and the district had also increased its employee and pension costs by $29 million annually by negotiating and approving (in Nov and Dec 2016) retroactive and mid-year, across-the-board salary increases of a combined 4%. In addition to the SERP (which was only cost saving in the early years), the district also made cuts to student programs and services, such as eliminating vice principals at elementary school sites, to fill the budget hole it had created.

So I suspect that the reason the SDUSD pension costs are lower than the state average has less to do with the claims listed and rather because SDUSD has significantly reduced the number of employees as a result of cuts to student programs and services.

ann 4 years ago4 years ago

So what impact did the 5% to 15% raises given to teachers have? You know, the ‘its for the children’ tax that Torlakson told districts could be spent on salaries AFTER the election….and they did.

Replies

SD Parent 4 years ago4 years ago

Well, at this point–where the rate for school districts is 19% of payroll–for every dollar in salary increase, a school district pays an additional 19 cents annually to CalSTRS. Another way of looking at it is that for every percentage increase in pay, that same percentage increase occurs in pension payments. So that 10% teacher raise comes with a 10% increase in annual CalSTRS costs.

Livermore Parent 4 years ago4 years ago

Kids in California are guaranteed a Free And Appropriate Education. If pension debt interferes with this right, then we should be able to force a district into Chapter 9 bankruptcy to restructure and extinguish some of that pension debt. Here in Livermore they have a waiting list for an English learners class because they say they don't have enough money. However our Superintendent Kelly Bowers made $410,433.71 a year last reported, … Read More

Kids in California are guaranteed a Free And Appropriate Education. If pension debt interferes with this right, then we should be able to force a district into Chapter 9 bankruptcy to restructure and extinguish some of that pension debt. Here in Livermore they have a waiting list for an English learners class because they say they don’t have enough money. However our Superintendent Kelly Bowers made $410,433.71 a year last reported, and our board president Craig Bueno has an annual pension of $212,728.32 so there is money for some things, just not our children. We should be putting high pensions and exorbitant salaries on a waiting list, not children.

Laura Manning 4 years ago4 years ago

How much would districts be paying into social security and other payroll taxes for these employees if there were no STRS?

Scott Petri 4 years ago4 years ago

I’m not sure how these facts can be true. Earlier reporting by Chad Aldeman shows that more than half of teachers do not receive any employer pension benefits because they leave before they are eligible. Just one in five stays on the job long enough to receive full benefits at retirement. https://www.educationnext.org/why-most-teachers-get-bad-deal-pensions-state-plans-winners-losers/ Are California pension rates significantly different from these national figures?